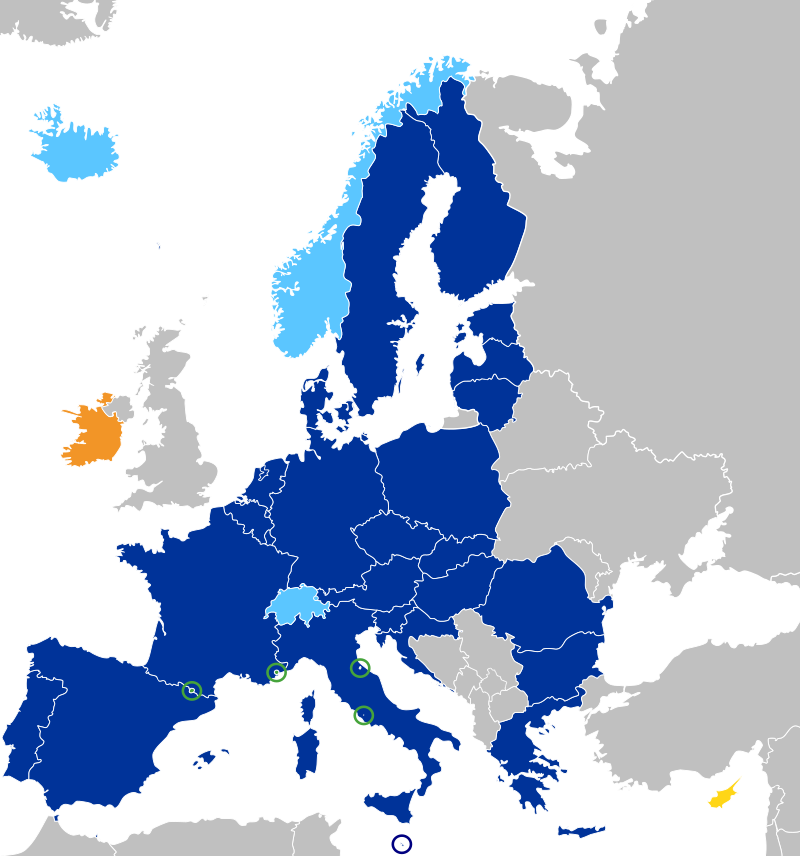

From 12 October 2025 the European Union will begin operating its long-planned Entry/Exit System (EES), a biometric database that replaces passport stamping for non-EU travellers and digitally logs every entry to — and exit from — the Schengen area. The stated aim is straightforward: to modernise border management, speed up passenger processing and detect irregular stays more reliably. But for UK haulage companies whose drivers cross the Channel frequently, the EES brings a new, unavoidable reality — one that could restrict working patterns, complicate planning and increase compliance costs.

Under the EES, fingerprints and a facial image will be recorded at border control and retained in the system for a defined period. Those biometric records are then used to calculate time spent inside the Schengen area and to automatically enforce the so-called 90/180 rule: non-EU nationals may spend no more than 90 days in any 180-day period in the Schengen zone. Until now, that rule existed on paper and was enforced by national border guards using passport stamps; EES makes the record-keeping automatic, granular and hard to contest. This automation is the particular worry for drivers whose work routines routinely take them across Europe for weeks at a time.

For many HGV drivers based in the UK, the nature of the job has always blurred the line between short visits and effectively living abroad for stretches. Routinely, drivers will do multi-stop runs across a mix of Schengen countries, return briefly to the UK, then head back out again. Under EES, those spells will be cumulatively recorded and summed. A driver who spends, say, three months working in France or Germany, returns home for a short break and then does another extended run, could quickly exceed the 90-day allowance and find themselves refused entry at a later checkpoint or face fines and other sanctions. Industry bodies warn that such outcomes are not hypothetical: once EES is operational the clock will be running and employers will be held to account for ensuring their staff comply.

It is important to be clear about what the rule does and does not say. The 90/180 count is cumulative and counts all time spent within Schengen, whether for work or private reasons. There is no implicit carve-out in the core EES legislation for professional hauliers; the system does, however, allow for national authorities to adopt complementary rules or exemptions in certain circumstances. Industry groups such as the Road Haulage Association (RHA), the British International Freight Association (BIFA) and Logistics UK have been lobbying for a formal professional-driver exemption or for a practical mechanism that recognises the realities of cross-border freight work, arguing that a sectoral solution is necessary to avoid damaging supply chains and causing driver shortages. So far, those calls have had limited success and member states are cautious about creating broad exceptions that could be abused.

Richard Smith, RHA Managing Director, said: “A couple of loads per week to Paris for example will soon rack up 90 days in 180, and that’s without taking the drivers own holidays in Europe into account which will also be included.

“Could this also open the door for yet more abuse of the cabotage system, which appears to be largely misunderstood or ignored by UK enforcement authorities? UK ports are filled with unaccompanied trailers arriving from EU. On a Sunday night some of the trailers will be accompanied by an EU registered truck which will work in the UK all week, tipping and loading trailers with international loads or on domestic work if quiet, only crossing back into the EU on a Friday to fill up with cheaper EU fuel, then repeat for 50 weeks. No input whatsoever into UK PLC…”

Practically, what should hauliers be doing now?

First, planning and tracking. Firms will need robust rostering and a reliable system to log drivers’ days in the Schengen area so that management can foresee and prevent breaches of the 90/180 limit. That may require new software, training for planners and drivers, and changes to contracts and rostering practices.

Second, advice and communication: drivers must understand that personal travel (holidays, family visits) also counts towards the 90-day total, so companies should advise staff to factor personal time into their calculations.

Third, contingency planning: hauliers should identify which routes and customers are most affected and consider alternatives such as shorter rotation patterns, use of local crews for last-mile work, or operating through establishments within the EU where drivers can be employed locally for periods without triggering entry checks. Several trade associations have published guidance and are maintaining dialogues with government and EU counterparts to seek workable arrangements.

Logistics UK’s Policy Manager – Trade, Customs and Borders Josh Fenton said, “The new system will automatically log time spent within the Schengen area, so it is essential that drivers ensure they comply with the current legal requirement of only spending 90 of the previous 180 days in the Schengen area. It is important to remember that both personal travel and commercial work contribute to the 90 days – personal holidays count towards the total. As the new system will automatically detect overstayers, drivers and operators need to ensure they remain compliant.

“The current 90/180 day rule does not support smooth trade between the UK and EU and we are calling for the UK government to seek an exemption from the EU for professional drivers. This will ensure they can continue to deliver the goods that businesses and consumers across Europe rely on and help drive growth. Until that happens, drivers need to comply with the legislation to ensure there is no disruption to their operations.”

The Department for Transport has produced a set of resources to help raise awareness among drivers and is encouraging operators to share on their social media channels. The resources can be downloaded here: EES Haulier Assets

There are immediate operational consequences to consider at ports and terminals. The practicalities of EES — kiosk locations, the need for drivers to step out of cabs to register biometrics ferry terminals, potential queuing times and the investment in infrastructure by operators — will change pre-departure routines and could add to turnaround time if not properly managed. Some operators and terminals are already investing in kiosks and reconfigured lanes to minimise disruption, but small-to-medium hauliers with lean margins may still face the bulk of the burden as they adjust to new time and staffing costs. There is, however, one exception to drivers having to leave their cabs and that is Eurotunnel, where the new checks will be accessible from within the cab.

Finally, there is a policy angle. The debate over a professional-driver exemption is both practical and political. Member states must balance border security with the functioning of crucial supply-chain sectors. UK authorities and trade bodies will therefore need to keep pressing for either sectoral flexibility or straightforward administrative solutions — such as an agreed mechanism that allows repeated short cross-border movements for drivers without those movements being treated as continuous residence. Until such remedies exist, hauliers should budget for change: compliance systems, potential delays and the human-resource headaches of managing drivers’ legal presence in Schengen.

The EES will modernise border control, but modernisation brings friction as well as benefit. For UK hauliers the key will be preparedness: accurate tracking, clear driver communication and active engagement with industry bodies and government to shape workable solutions. Without that, businesses risk operational disruption and unexpected costs when the EES clock starts to tick.

Mark Salisbury, Editor